- Think About It

- Posts

- The Freedom of Loneliness & The Safety of Being Misunderstood

The Freedom of Loneliness & The Safety of Being Misunderstood

A poetic contradiction that challenges everything we believe about being known and being alone.

Have you ever felt relief when someone didn't understand you?

And do you find a sense of comfort in your loneliness?

I know, I know, it sounds absurd. We spend our lives trying to be seen, heard, and understood. We choose our words carefully, craft our social media posts, and sometimes even change ourselves to fit what we think others want to see.

And loneliness is usually cast as suffering. A negative feeling that you should try to avoid by all means.

But what if I told you that one of history's greatest poets argued that being understood might actually be a form of enslavement? And there’s freedom in loneliness?

And what if he was right?

Hello to all the readers. This is the eighth edition of Think About It, and today we will be looking at another of Kahlil Gibran’s literary gems.

And I have found both freedom and safety in my madness; the freedom of loneliness and the safety from being understood, for those who understand us enslave something in us.

But let me not be too proud of my safety. Even a Thief in a jail is safe from another thief.

These are the concluding lines from Gibran’s first piece in The Madman.

These lines are beautifully twisted in the most thought-provoking way. So, first, it’s really important to understand what madness (and madman) really means.

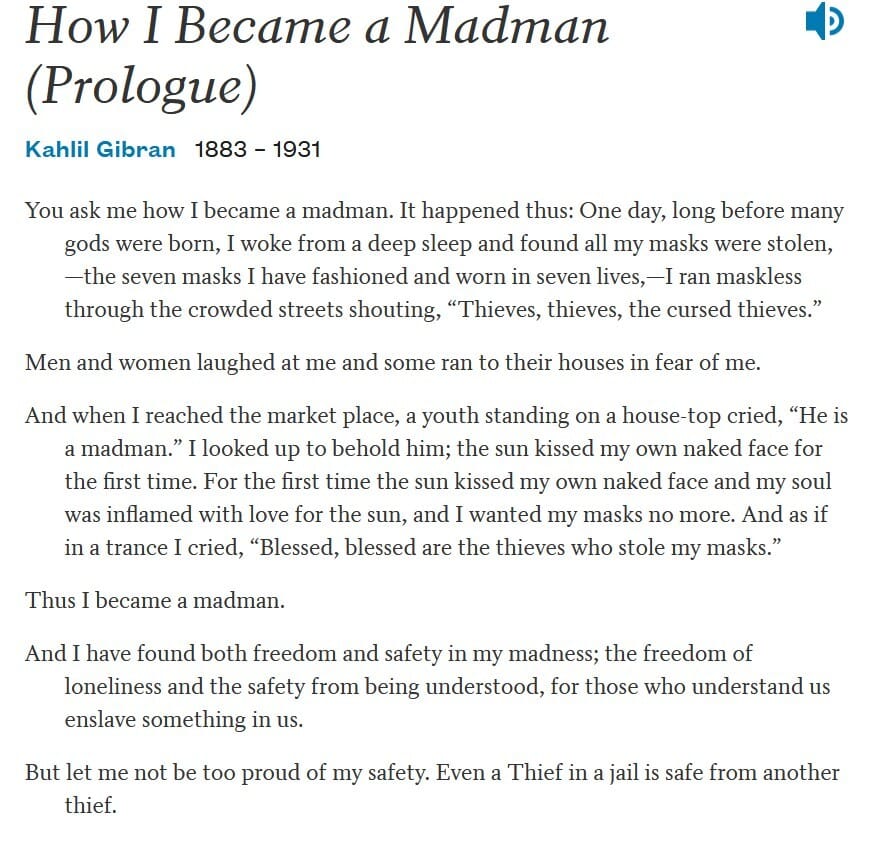

And for that, I think it’s best if you just quickly go through the full piece. (see screenshot below).

Credits: poets.org

The masks he refers to in the beginning represent societal roles. And when he says all his “masks were stoles”, that means it’s his awakening and realisation that he can’t hide behind masks anymore.

He is being called a madman because he’s breaking the norms.

It’s clear that for Gibran, ‘madness’ means:

Unconventionality: Thinking, feeling, or perceiving the world in a way that deviates significantly from societal norms or common sense.

Eccentricity: Being unique, peculiar, or outside the mainstream.

Deep introspection: Being so deep within one's own thoughts and perceptions that it separates them from others, which might appear "mad" to the outside world. (He did not resist the youth calling him a madman.)

Artistic/philosophical perspective: The perspective of a visionary or a mystic, whose insights seem irrational to the uninitiated. (“the seven masks I have fashioned and worn in seven lives,”)

Now, let’s shift our focus to the concluding lines because this is where it gets twisted, absurd, and a bit uncomfortable as well.

Gibran basically says that he has discovered a sense of liberation and protection within his state of ‘madness.’

Beautiful (or absurd) contradictions

Now, this line, “the freedom of loneliness,” hurts, doesn’t it?

But here, Gibran doesn’t mean loneliness in conventional terms. Loneliness, to him, is solitude without surveillance.

When you're truly alone, you're not bound by others' expectations, judgments, or demands. You're free to be entirely yourself, without the need to conform, explain, or perform for anyone else. So, Gibran says, there's liberation in not having to cater to social dynamics or compromise your inner truth for the sake of companionship.

There are two kinds of loneliness: one is when someone feels lonely because of a situation or circumstances. And the other one is when someone chooses to be lonely.

It’s the difference between being locked in a room… and closing the door yourself.

Gibran, obviously, refers to the kind of loneliness that one chooses.

Next, “the safety from being understood” is the line where it gets twisted and makes you think hard. It is a paradox and the most intriguing part. Why did Gibran think that understanding was a threat?

Well, he teases the answer in the next line:

for those who understand us enslave something in us.

This is the explicit link. Enslaving something could mean:

Loss of authenticity: If someone fully understands you, they might gain a certain power over you. They might see your vulnerabilities, your quirks, your deepest fears, or even your true, raw self that you wish to protect.

Loss of uniqueness/fluidity: To be understood often means to be categorised, defined, or put into a box by others' perceptions. Gibran suggests that being perfectly understood can limit you. This can prevent you from evolving or changing without their perception becoming a cage. They understand who you were, not necessarily who you are becoming.

The burden of expectation: When someone truly "gets" you, they might then have expectations for you based on that understanding, which can feel like a burden or a form of confinement.

Loss of Mystery/Depth: Part of a person's richness can lie in their inscrutability. If you are entirely transparent, perhaps some of your depth, mystery, or even your "madness" (uniqueness) is lost.

In the same book, he writes something similar later in the poem Defeat:

Defeat, my Defeat, my shining sword and shield,

In your eyes I have read

That to be enthroned is to be enslaved,

And to be understood is to be leveled down,

And to be grasped is but to reach one’s fullness

And like a ripe fruit to fall and be consumed.

He is saying that the higher you rise (or perhaps the more you get understood), the more you're trapped by expectations, to manage your image or perception of what others need you to be.

He writes, “To be understood is to be leveled down,” to provide another answer to why being understood can be a threat. Here, “leveled down” simply means being reduced to others' perception or understanding of you.

Now, getting back to the last line of the original quote, if you think that freedom in loneliness and safety from being understood is absurd, you are not wrong. That actually shows that he romanticizes inner exile and clings to ambiguity.

But then he says:

But let me not be too proud of my safety. Even a Thief in a jail is safe from another thief.

This is where he turns this whole thing on its head, right? I told you, it’s twisted!

With that final line, Gibran isn't celebrating his "madness" and isolation; he's acknowledging its limitations with brutal honesty. He's both the person justifying his choices and the person questioning those same choices.

The thief analogy is devastating in its simplicity. When Gibran says he’s “safe from being understood,” he compares it to how a thief feels safe in jail. What he means is: yes, he’s protected, but only because he’s cut off from others.

He’s pointing out that not being understood can feel like a kind of prison. You avoid being judged or hurt, but you also miss out on real connection, love, and the deep meaning that comes from being truly known.

It’s a kind of safety, but a very lonely one.

What makes this quote extraordinary is Gibran's refusal to let himself off the hook. He acknowledges both the necessity of his choice AND its cost. It's like he's saying, "I'm going to be honest about why I made this choice, honest about what it gives me, and honest about what it costs me."

This is what great literature consists of—the willingness of the writer to hold contradictions and uncomfortable truths simultaneously.

That’s it for this edition.

I hope it was worth your time.

(On that note, let me know if you would like slightly shorter versions next time.)

See you next week

Until then

Stay curious

Zaid

Reply